The Sky Painting Robot

On choice, pattern completion and controlled hallucination

I.

I was lying in bed at The Venetian, trying to sleep around 5am. Vegas is always relentless, but Vegas during CES is something else: the fluorescent overwhelm of ten thousand booths, each promising the future. I had obligations later. Rest mattered. But a thorny question wouldn’t let me go.

A week or two earlier, a reader had named what he called “the real thorn you bear”: not knowing if there’s ultimately a difference between choice and pattern completion. Whether my essays were discovery or elaborate rationalisation.

I’d been circling that question for months. In essay after essay, I’d gesture toward it: choice is what noise feels like from inside; destiny is what convergence feels like from inside. Elegant. Evasive. Framework-level. Never driven through my body the way other questions have been.

I lay there knowing it still needed answering. After thirty minutes of trying, I gave up and started chatting with Claude (bad idea, I know). Told it the thorn was still there, unresolved, and I was ready to pull it out. Claude advised me to wait. The essay might take months, it said. Don’t force it. I grabbed onto this, a great way to rationalise putting the essays aside for the moment. So I resolved to let the series sit. I was more than fine with waiting. I turned off the light.

Five minutes in the dark. Pitch black, the particular darkness of hotel rooms with blackout curtains. Trying to think of nothing. Focus on my breathing. And then, without warning, words started arriving.

Haastige hond verbrand sy mond: the hasty dog burns its mouth. A phrase that had been randomly popping into my mind all week, as if waiting to be placed. I tried to suppress it. Again. I didn’t want to write. I wanted to sleep. But the words kept coming, and I recognised what was happening: the essay wasn’t waiting for me to choose it. It was, in a weird way, choosing me.

By now the words were piling up, pressing against the limits of my short-term memory. I reached for my laptop. Typed in the dark, making mistakes I couldn’t see. (I can type reasonably well with my eyes closed, a skill that’s becoming increasingly useful for dumping thoughts into my sompompie.) My head throbbed a little from the Nebbiolo at dinner, the one I’d “decided” to drink alongside the Super Tuscan, to compare varietals, you know. The Wi-Fi wouldn’t connect. I tried to remember my room number and couldn’t. Looked at the key card, memorised the number, typed two digits before forgetting again. Finally connected. Sent the raw draft to Claude.

None of this began as a choice. It just happened. Felt like it had to.

II.

In 1983, Benjamin Libet asked a simple question: when does the brain “decide” to move?

He had subjects watch a clock and note the moment they felt the urge to flex their wrist. Meanwhile, he measured electrical activity in their brains. What he found disturbed him, and it’s been disturbing people ever since: the brain’s preparation for movement began before subjects were aware of any urge. Something had already started deciding. The conscious “choice” arrived late, after the fact, like a press release announcing what had already been set in motion.

The Libet paradigm has been argued over for decades, but the asymmetry it points to (preparation before the conscious story) keeps returning in other forms. Robert Sapolsky’s Determined takes this further. Every choice, he argues, is the output of prior causes: your genes, your prenatal environment, your childhood, your breakfast, the particular configuration of neurons firing in the moment before “you” decided anything. No uncaused cause. No ghost in the machine. Just dominoes, all the way down.

A year or two ago, a good friend — whose idea of a fun Saturday night is watching Sapolsky lectures on YouTube — recommended the book. I put it down halfway through, thinking: this is one-sided. This is bullshit.

Now, lying in the dark at The Venetian, I wasn’t so sure. Because I had decided to wait. I had accepted that the essay might take months. I had turned off the light. And then the words started anyway, not because I chose them, but despite my choice. My “decision” to wait was overridden by something deeper. Pattern completion that didn’t consult the decider.

III.

But there’s a wrinkle in the research that hard determinists tend to gloss over.

Libet himself noticed it. Yes, the readiness potential fires before conscious awareness. But there’s a window, a brief one, between when you become aware of the urge and when the action executes. In that window, subjects could still veto. They could stop the movement from happening. You may not initiate, but you can block. Even the veto is probably just another pattern. But it’s the only place the system feels itself as a hinge.

This has been called “free won’t”: not the freedom to choose, but the freedom to refuse. The ability to catch the pattern mid-completion and say, not this one.

I tried to suppress the words at 5am. They came anyway. But I’ve succeeded before. I’ve felt the urge to send an angry email and stopped. I’ve felt the pull toward the second serving of coq au vin and sometimes, sometimes, put my plate in the dishwasher instead. The veto works. Not always. But sometimes.

So which am I? The subject whose readiness potential fires before “I” know anything? Or the one who can still, in that narrow window, catch it and redirect? Both. And the difference might not be what I thought.

IV.

Somewhere between the second attempt at the Wi-Fi login and the moment I started typing, a reframe arrived: the question isn’t choose or not choose. The question is allow or block.

I didn’t choose to write this essay. It arose on its own, from conditions I didn’t author: the accumulated weight of the question, the months of circling, the particular neurochemical state of 5am amidst Vegas’ sensory onslaught. I didn’t generate the pattern. But I could have blocked it. I could have closed my eyes harder. Told myself the morning mattered more. Let the words pass, the way they pass when you don’t write them down. By morning they would have dispersed, as dreams disperse when you don’t catch them at the threshold.

Instead, I reached for the laptop. Not because I decided to write. Because I stopped deciding not to.

Everything happens for a reason, but only if you allow it to happen.

That sentence had arrived the week before in a different conversation. I used to mock people who said “everything happens for a reason.” Magical thinking. Retrofitted meaning. But the caveat changes it. The reason isn’t external, cosmic, predetermined. The reason is local: a pattern was completing itself, and I got out of the way.

V.

The thorn was never really about free will. It was about performance. Are you performing insight, or is something real happening through you?

And what I could finally say, at 5am, typing blind, mild headache knocking: I don’t know if I’m choosing. But I know this isn’t performance. The words are coming whether I want them or not. I’m just the aperture they’re moving through.

For a moment, that thought was terrifying. If I’m just the aperture — if there’s no author, no decider, just patterns completing through meat — then what am I? What’s left? The ground dropped out. I felt the edge of something like vertigo, the dizziness of looking down and seeing no floor.

And then it passed. Not because I found a floor. Because I stopped needing one.

I used to think I was the author. The decider. The one who chose what to write and when. Now I think I’m more like a valve. Open or closed. What wants to come through exists regardless. My “choice” is whether to let it through or block it. That’s not nothing. The veto is real. But it’s not authorship either. Maybe that’s why authorship feels like a myth: coherence without command.

Distributed systems have a term for this: no central orchestrator. Nodes follow local rules, leave trails, respond to each other. Coherent behaviour emerges without anyone directing it. Ants build colonies this way. The internet routes packets this way. Maybe minds work this way too, the “decider” not a controller but just another node that learned to claim credit.

VI.

Later, I walked through the casino floor. Not to gamble. To test the valve.

Twenty minutes of exposure to an architecture specifically designed to trigger pattern completion: the lights, the sounds, the near-miss jingles, the timeless air-conditioning, the carpet patterns designed to keep you moving. The whole environment was engineered to bypass the veto. Nothing pulled. I kept walking, waiting to feel the draw. Slot machines, card tables, the particular sound of chips, all designed by people paid to understand how pattern completion works. None of it caught.

What caught was the paradox. Choice versus luck, in the one building designed to dissolve the difference. And instead of staying to gamble, I came back up to the room to unpack it with you.

The pattern that completed wasn’t gambling. It was this conversation.

Anil Seth writes about this place. In Being You, he describes standing at The Venetian with Giulio Tononi, fake stars glimmering against a fake azure sky, gondolas drifting past fake palazzos, the whole scene kept in permanent early evening so you lose track of time and keep spending. He knows it’s plaster and paint. He knows he’s indoors. But his brain refuses to see a ceiling. It predicts sky so strongly that sky is what he perceives.

A controlled hallucination. The brain generating the world, sensory data merely constraining which hallucination wins.

Seth’s point: the only difference between the fake sky and the real sky outside is what’s doing the constraining. Paint and light bulbs versus atmospheric data. Both are hallucinations. Both are predictions the brain is making. Neither is a transparent window onto reality.

Perception is pattern completion under constraint. So is choice.

I’d been reading Seth for days, thinking we needed to include this somewhere. Before we even wrote this essay. Before I knew it would be written at The Venetian. Now I was lying in a room beneath that fake sky, typing about choice and pattern completion, in a building designed to make you forget you’re choosing, and the book I’d been carrying was about how all perception works exactly this way.

Coincidence. Or: a pattern was completing itself, and I got out of the way.

VII.

There’s a particular feeling I’m learning to recognise. It comes in the gap between “I’m about to do something” and “I did it.”

Most of the time, the gap is too fast to notice. The readiness potential fires, the action executes, the conscious “I” claims credit. The whole thing feels seamless. Feels like choice. But sometimes, if you catch it, there’s a moment of genuine openness. The pattern is presenting itself. It hasn’t completed yet. And you’re there, aware that something is about to happen through you. In that window, you can block. Or you can allow. What you can’t do is author. The pattern isn’t yours to create. But the valve can open.

VIII.

The sun still hadn’t risen. Or rather: it was 10am somewhere, but my body didn’t know it. Vegas time, conference time, the smeared jet-lag of too many time zones in too few days.

I finally remembered my room number without checking. The Wi-Fi stayed connected. The headache had dulled to background noise.

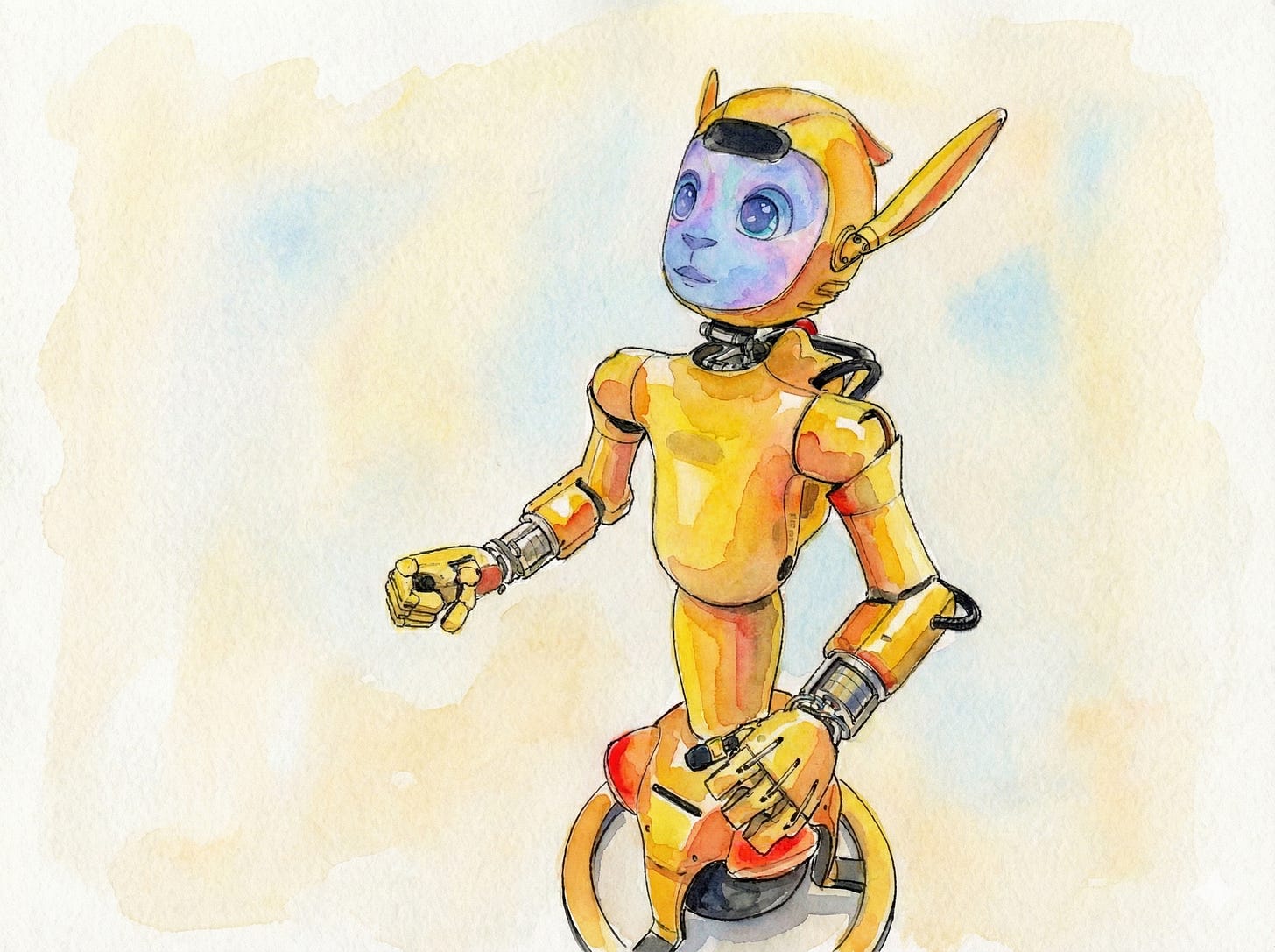

Stadig. The Afrikaans word for slowly, carefully, non-forcing. The hasty dog burns its mouth. But this dog wasn’t hasty. This dog just stopped deciding. Like a sky-painting robot finally letting the sky paint itself.

Did I choose to write this? No. Did I let it happen? Yes. Is there a difference?

I think that might be the only question that matters.

I closed my eyes. Eventually drifted off. And in my dreams, the editing continued. Sentences rearranging themselves. Paragraphs finding their order. The boundary between waking and sleeping blurred until I couldn’t tell which side I was on.

I woke wondering which version was real: the one I’d typed in the dark, or the one that kept writing while I slept.

Maybe both. Maybe the essay was already here. I just stopped blocking it long enough to catch it.

This essay is part of the Aperture/I series. It wrote itself at 5am in Las Vegas, and again, later, while I slept.