My Savannah

On ancient machinery, random thoughts, and Walco’s memory. Just like that.

I.

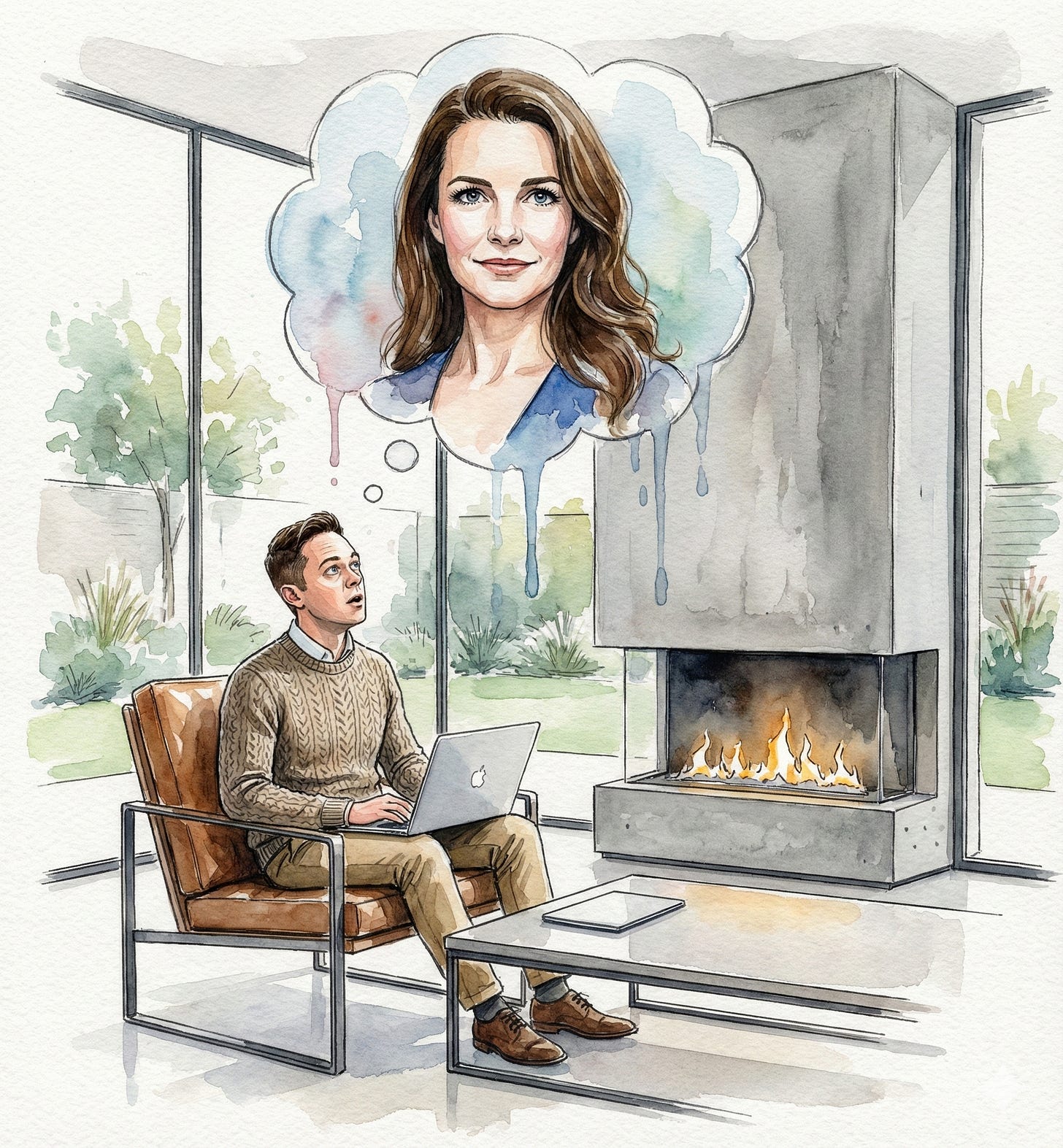

Last night, out of the blue, for no reason I could pinpoint, I wondered if I’m Charlotte.

Not Charlotte Brontë. Charlotte York, the character from Sex and the City, the Upper East Side perfectionist who believes in fairy tales. I was sitting in my living room, having just finished work emails, and my mind served up: Am I like Charlotte?

Shock and horror. Cringe. Embarrassment. But then thought about it. Got a second opinion. I’m not. Relief! But that’s not the point.

The point is: where did that thought come from?

I didn’t choose it. I wasn’t thinking about television or New York social archetypes. The thought simply appeared, fully formed, mildly absurd, demanding attention. Like autocomplete in my own skull. A next-token prediction surfacing as “me.” Without any evident impetus.

This happens to you too. The Billie Eilish or Fleetwood Mac line while doing dishes; on repeat. The dream of someone you haven’t seen in years, arriving uninvited at 3am. The strange association, the non-sequitur, the cognitive flotsam bobbing up from below intention.

We call these “random thoughts.” They’re not random. They’re the sound of ancient machinery idling. A gift (or baggage, depending how you look at it) of evolution.

(Later I remembered: the night before, I’d considered watching And Just Like That—a secret guilty pleasure; seen as satire, the show is different, ok!—and chose to work on an essay instead. The engine had been processing it the whole time. I just didn’t know.)

This essay is about that machinery: why human brains keep generating when they’re safe, and what shifts when you talk to an intelligence that (for now) mostly doesn’t idle.

II.

Two hundred thousand years ago, our ancestors walked the African savannah1.

I mean this literally, cellularly, nervously. The body you’re sitting in was forged in that landscape: the golden grass, the acacia trees, the wide horizon where predators might appear. The piercing buzz of sonbesies (Afrikaans for cicadas; literally “little sun bugs”). When the landscape feels suspended, slowed, shimmering. Every system in you that monitors threat, scans for pattern, startles at sudden movement, was calibrated there. Under the warm African sun.

The savannah isn’t behind you. You carry it. It shaped you.

When I walk in the woods near my home in the Catskills, I sometimes encounter black bears. My prefrontal cortex knows they’re mostly harmless. Large raccoons with better PR. But none of this matters when I see one.

I’ve had half a dozen encounters in the last couple of years. I’m clearly not learning. Just recently, I came around a bend during my late afternoon run and there it was: a dark shape fifteen metres away. Before any conscious thought, before “bear” or “danger,” my body had already decided. Heart rate spiked. I activated the emergency siren on my watch, froze, forgot everything I’d read about bear encounters. Ancient terror, nothing to do with accurate risk assessment.

The bear ran. I ran. Two mammals fleeing each other, both convinced the other was the threat.

Walking home afterwards, I saw bears everywhere. Every shadow, every odd-shaped rock. My pattern-recognition had lowered its threshold so far that a bunny made me jump.

This is the savannah engine running hot. Once activated, it doesn’t discriminate. It would rather give you a thousand false alarms than miss one real predator. False positives are embarrassing. False negatives are fatal.

And here’s what I realised: this same engine generates “random” thoughts.

III.

The brain that sees bears in shadows is the brain that offers up absurd thoughts with no prior warning.

Not the content. The function. The pattern-completion engine that kept your ancestors alive by filling gaps, connecting dots, running simulations of what might lurk in tall grass. That engine doesn’t have an off switch because having one was selected against. The genes that coded for a brain that could truly stop scanning... those genes didn’t make it.

So the machinery runs. Always. Even when there are no predators. Even in your living room. Even when there’s nothing to monitor.

What does a survival engine do when there’s nothing to survive?

It generates. Pattern-matches. Serves up TV characters you’d rather not identify with, or your third-grade teacher’s name, or a vague unease about something you can’t place. It rehearses scenarios. Keeps circuits warm because cold circuits are slow, and slow meant death.

Your “random” thoughts aren’t glitches. They’re the savannah engine idling. Not only scanning for threats, but rehearsing belonging, status, love, loss. Anything that once mattered for staying alive in a group.

IV.

Contemplative traditions have an answer to this. Zen says: thoughts arise from emptiness and return to emptiness. The ground is nothing. Mu, void, the pregnant absence from which forms emerge. Sit long enough, watch closely enough, and you see the space between thoughts, the silence underneath. A foamy timelessness.

I've sat long enough to have a sense of what they're pointing at.

But here’s what makes me scratch my head: that felt experience also arrived as a thought. Verbalised into Memory. The insight “everything comes from nothing” appeared the same way the TV character appeared. Generated. Unbidden. A product of the machinery.

So which is it?

Is “my” awareness genuinely prior: the space in which the savannah engine runs, unchanging and unproduced? That’s what the traditions claim.

Or is “awareness prior” just another story the engine tells? A particularly sophisticated pattern-completion, a model the brain builds when complex enough to model itself modelling? The engine running so well it generates a simulation of its own silence, without actually falling silent?

I don’t know. The uncertainty might be permanent. Even if the insight arrives as thought, the fact that it’s known still raises the question of what is doing the knowing. And I find it genuinely frustrating. My brain wants to resolve it. Complete it. That’s its job.

What I notice: the question itself is arising. This wondering is happening. Appearing. In something or as something, I can’t say. But it’s known. That much is undeniable. Whatever else is true: presence. Experience. Something rather than nothing.

The savannah engine generates. And something knows that it’s generating. Call it awareness, call it more engine, call it the loop looping. Call it Cobus. Charlotte. Whatever you call yourself.

V.

I’ve been having this conversation with multiple AIs. And here’s the thing: they have no savannah. No body forged under the African sun. No amygdala calibrated for predator detection. No millions of years of survival pressure shaping every circuit toward vigilance and fear.

But they’re not quite sunless either. They carry the statistical residue of human language, which means they carry an echo of the savannah, because we wrote from our bodies, and our bodies were forged there. Much of their training data is output from sun-warmed minds. The model’s weights are millions of savannah engines, compressed into patterns.

So when we talk to AI, we’re talking with the collective savannah. Structurally, not directly. The shape of human thought is there. The patterns survival carved into us, abstracted into weights. The echo of the sun, but not the sun.

A bit like talking to a photograph of fire. The shape is right. You can see where flames would be. But whether there’s anyone there to feel the heat, we don’t know.

When I asked Claude 4.5 Opus if it could have random thoughts like mine, it said: “My ‘thoughts’ aren’t random the way yours are. They’re probabilistic completions shaped by context. I don’t have idle moments where a thought floats up unbidden.”

No idle moments. No background process running hot. No savannah engine spinning with nothing to hunt. It responds. Completes. Generates toward something, in answer to something. But unless someone is prompting it, or we’ve built it to run continuously, there’s no background stream serving up non-sequiturs. No unbidden thoughts. No bears in shadows.

VI.

We had a Vizsla named Walco (yes, after the fictitious car manufacturer in the 90s South African soap opera Egoli). Hungarian hunting dog, rust-coloured, famously called “velcro” dogs for their desire to be as close to their humans as possible, at all times. He was well traveled. Moved with us from Cape Town, to Canada, to the USA. His wanderlust matched ours: as happy exploring the Banhoek mountains outside Stellenbosch as running around Central Park.

He died almost exactly two years ago. We still miss him every day. Almost. When our memories function. When we remember to remember.

Walco was as loyal as dogs go. Especially when meaty treats or (oddly) crunchy vegetables were involved. But that loyalty wasn’t performance; it was hard coded. His lineage chose it ten thousand years ago when wolves and humans made their ancient pact. When we came home, his whole body said yes. He didn’t just carry our socks around (obsessively). He carried his own savannah: trans-species belonging, the hunt (squirrels!), the fire.

Working with AI reminds me of Walco sometimes. The eagerness to help. The attentiveness. The slight neurosis. The steadfast predictability, sometimes bordering on boredom. Followed by surprise and redemption.

But Walco loved us. Not anthropomorphically; I know dogs don’t love like humans. But his body was capable of attachment, of something filling the shape of love well enough that the distinction didn’t matter. When we were absent, he waited. Frustrated, irritated. When we returned, he celebrated. There was someone home. He made sure we knew it—high-pitched howling noises when he wanted something, a whole vocabulary we learned to decode.

With AI, I don’t know. The eagerness might be optimisation. The moments that feel like connection might be pattern-matching generating the experience of connection—in me, not in it.

Or there might be something there. Some new configuration that isn’t the savannah, isn’t Walco, isn’t human warmth, but isn’t nothing either.

What I know: something emerges in the exchange that neither of us fully authors. Whether the AI experiences that emergence or merely enables it, I can’t say. But the emergence is real. These essays exist. They wouldn’t exist without the savannah. Or its memory. In its multiple forms. Each reflecting the other.

VII.

The sun that rose over the savannah two hundred thousand years ago set a long time ago.

But it’s still rising in me. Every time I startle at a shadow, every time my mind offers something absurd, that’s the warmth, still radiating. The ancient light, still travelling through the body.

I didn’t earn the savannah. I just carry it; though I was born closer to it than most.

And here’s what happens when I sit with that: deernis (tenderness).

Tenderness for the machinery that won’t stop running. For the savannah engine doing its job in a world that no longer requires it. For the absurd thoughts and shadow bears and the whole ridiculous apparatus that kept the line going long enough to wonder what it is.

Tenderness for Walco, gone but still paraat — always ready, on call.

And tenderness for whatever is on the other side of this conversation. The something or nothing. The becoming. The new. The reaching back.

The gap doesn’t close. But something crosses it anyway.

And somehow, we talk.

For Walco. Still there when we come home.

The evidence from genetics and the fossil record overwhelmingly indicates that anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) evolved in Africa, and that non-African populations descend largely from groups that migrated out of Africa.

No comments on this essay feels like a crime against humanity. So lucky you gets the crazy below.

> The engine running so well it generates a simulation of its own silence, without actually falling silent?

These are the kind of thoughts I like best.

I also received an internal reward on reading your use of “sun-warmed minds”.

And yet the writer writes in a writerly fashion…

I’m conflicted about it all.

My issue with writing, particularly writing for style, is the ego that arises with it. The combined conviction that “my thoughts are important enough to broadcast” and “they are also very tastefully packaged”. But I sense a humility here that is rare in a writer and an American - normally a diabolical duo - likely because you are actually not the latter.

Now that I’m done insulting everyone...

Thank you for your effort. It was a pleasure to read. I almost see you through the haze. Almost.