The Wrong Question

What Seth Gets Right (And What He Might Be Missing)

Anil Seth’s “The Mythology of Conscious AI” arrives at the right moment. As breathless proclamations about machine consciousness multiply (engineers claiming their chatbots feel things, researchers suggesting consciousness has already emerged in silicon), we need voices insisting on rigour. Seth provides exactly this. His essay is a careful dismantling of the assumptions that make conscious AI seem inevitable.

I agree with most of it.

But I think the essay, for all its clarity, might be answering the wrong question. Or rather, it might be answering the question everyone’s asking while missing the question we should be asking instead.

Here’s the thesis I want to defend: The question isn’t whether AI is conscious; it’s what kinds of minds we’re building—and what kinds of moral and relational fields they create.

Where We Stand Together

Let me begin with the substantial common ground.

Seth argues that brains are not computers. I agree completely. The metaphor of mind-as-software running on brain-as-hardware has been productive, but it obscures more than it reveals. Biological brains have no clean separation between what they do and what they are. The materiality matters. Neurons aren’t logic gates made of meat. They’re parts of a living system that has to keep itself going: metabolically, continuously, irreversibly.

Seth argues that computational functionalism—the assumption that implementing the right computation suffices for consciousness—is a strong claim that should not be taken as given. I agree. This assumption has become so pervasive that it functions as invisible background, rarely examined. Seth brings it into the foreground where it belongs.

Seth argues that simulation is not instantiation. A computational model of digestion doesn’t actually digest anything. Weather simulations don’t make things wet. Why assume consciousness is different? This is a genuine question, not a rhetorical one, and Seth is right to pose it.

Seth argues that we should be skeptical of reports from AI systems claiming inner experience. These systems are trained to produce humanlike outputs; producing humanlike claims about inner experience is exactly what we should expect, whether or not anything is actually experienced. I agree this warrants serious caution.

Where We Might Diverge

Here’s where I want to push back, gently.

Seth frames the question as: “Is AI conscious?” He then provides compelling reasons to think current AI is not. But I think this framing already concedes too much to a binary that may not carve reality at its joints.

The question assumes consciousness is a single thing that systems either have or lack. But what if consciousness admits of degrees, kinds, and configurations that don’t map onto a simple yes/no? What if the question “Is AI conscious?” is as malformed as “Is a virus alive?” The answer to the virus question isn’t yes or no; it’s that the binary categories of “living” and “non-living” don’t cleanly apply. The interesting work is understanding what viruses actually do, not forcing them into pre-existing boxes.

Seth is arguing about substrate: wetware versus silicon, biology versus computation. I want to argue about architecture: what configurations create what kinds of reflexivity—the capacity for a system to model and respond to itself—regardless of where we draw the substrate line.

The Simulation Objection

Seth’s strongest move deserves direct engagement: simulation is not instantiation. A computational model of digestion doesn’t digest anything. Weather simulations don’t make rain. Why should a simulation of consciousness be conscious?

The aperture framework doesn’t claim AI is simulating consciousness. It claims certain configurations—regardless of substrate—create apertures. The question isn’t whether silicon is “really” running consciousness the way a stomach “really” digests. The question is whether the relevant properties obtain: recursive self-modelling, global integration, temporal depth.

But there’s a deeper response. The simulation objection assumes we know what “instantiation” would mean for consciousness. Digestion has clear success conditions: food goes in, nutrients are extracted, waste comes out. We can check whether those conditions are met. What are the success conditions for consciousness? If we say “there must be something it’s like,” we’ve presupposed the answer. If we say “the right functional organisation,” we’ve granted functionalism.

Seth rejects functionalism. Fair enough. But his alternative—that biological, metabolic, living processes are required—is also a strong claim. It’s not obviously true that carbon is magic and silicon isn’t. It’s a hypothesis about which substrates can support which configurations.

The aperture framework is agnostic on substrate but not on configuration. It predicts that systems with genuine temporal accumulation, embodied constraint, and constitutive stakes will exhibit different properties than systems without them—not because carbon is special, but because those configurations create depth. Current AI lacks that depth. That’s the critique, and it doesn’t require the simulation/instantiation binary to land.

What it does require is admitting we don’t yet know what configurations are sufficient. Seth is confident biology is necessary. I’m genuinely uncertain. The uncertainty itself is the honest position.

A Different Framework

I’ve been developing what I call the Aperture Framework in previous essays. The core idea: consciousness isn’t a substance that brains produce or contain. It’s what happens when certain configurations of matter become reflexively aware.

Think of it like a camera aperture. The aperture doesn’t create light; it allows light to pass through in particular ways. Similarly, certain configurations of matter don’t create consciousness from nothing; they allow something to become reflexively manifest.

On this view, the question isn’t “Does AI have consciousness?” but “What kind of aperture is AI? What does it let through? What does it exclude?”1

This reframe matters because it shifts the focus from presence/absence to configuration/capacity. A smartphone camera and a large-format film camera are both apertures, but they’re radically different in what they can capture. Neither is “more of a camera” than the other; they’re different configurations with different affordances.

The Metaphysical Move

Here I need to make an important clarification. Seth’s position, despite his criticisms of computational functionalism, remains fundamentally physicalist. He believes consciousness arises from physical processes in the brain; the question is which physical processes and how.

The aperture framework rests on a different metaphysical foundation: dual-aspect monism2. This isn’t a minor technical distinction. It changes everything.

Physicalism holds that matter is fundamental and consciousness is derivative. Even sophisticated versions must explain how experience emerges from, or reduces to, physical processes. This is the hard problem: no matter how completely we describe neural correlates, the question “why is there something it’s like?” remains.

Dual-aspect monism proposes something different. Matter and consciousness aren’t two different kinds of stuff, nor is one derived from the other. They’re two irreducibly different descriptions of one underlying process. Neither produces the other; they’re co-original aspects of reality.

Think of a coin. The front doesn’t produce the back. Asking “how does heads generate tails?” is malformed. They’re both aspects of the same coin, neither more fundamental.

On this view, the hard problem dissolves not because it’s solved but because it rests on a false premise. There’s no mechanism by which matter produces consciousness because matter and consciousness aren’t in a production relationship. They’re complementary descriptions of what’s actually happening.

The Real Problem with the “Real Problem”

Seth has proposed replacing the “hard problem” with what he calls the “real problem”: explaining why consciousness has the particular character it does. Why does red look like that? Why does pain feel like this? He suggests we can make progress on these questions through neuroscience without solving (or even engaging) the hard problem.

This is methodologically strategic, and I appreciate pragmatism. But I think it brackets the metaphysical question rather than answering it.

Seth compares consciousness to vitalism: we once thought “life” required some special vital force, but biology dissolved the question by explaining living processes without it. He suggests consciousness might be similar; perhaps the “hard problem” will simply dissolve as we understand more.

But there’s a crucial disanalogy. Vitalism dissolved because there was nothing the question was pointing to. There was no vital force; life just is certain biochemical processes. The question evaporated because its presupposition was false.

Consciousness is different. The hard problem doesn’t rest on a mistaken presupposition about special substances. It rests on the brute fact that there is something it’s like to be you, reading this sentence. That fact doesn’t dissolve when we explain neural correlates; it’s what demands explanation in the first place.

Seth’s “real problem” approach is essentially: let’s map correlations and set aside the question of why there’s experience at all. That’s legitimate scientific methodology. But it’s not philosophical progress on the hard problem; it’s a decision to work around it.

Dual-aspect monism offers something different. It says the hard problem was generated by assuming matter and mind are different kinds of things requiring a bridge. Remove that assumption and the problem changes character. Not dissolved through explanation, not abandoned through pragmatism, but reframed through different metaphysical commitments.

Life Creates Depth

Here’s where Seth’s insights become most valuable, even within the aperture framework.

Seth emphasises that biological life is constitutively temporal. Organisms exist by maintaining themselves against entropy; they have a past they emerged from and a future they’re organised toward. This creates what we might call existential depth: stakes, vulnerability, the possibility of flourishing or suffering.

Humans learn under constraint. Embodiment. Temporal sequence. Metabolic cost. Survival stakes. When you learn “hot,” you don’t learn a token correlation; you learn a sensorimotor loop with consequences. You reach toward the flame. You feel pain. You update. Reality pushes back in ways that cannot be gamed.3

Most deployed AI systems, as used today, lack this entirely. Large language models have little constitutive continuity between conversations. No metabolism to maintain. No death to avoid. No accumulated history that constitutes an ongoing self. Each interaction is, in a meaningful sense, the first and last. Even when memory scaffolding exists, it’s not obviously identity-constituting in the way biological memory is.

This matters for the aperture framework. If consciousness involves reflexive self-modelling, the depth of that self-model matters. A system that models itself as a persistent entity navigating time, maintaining boundaries, facing mortality, is a different kind of aperture than one that models itself (if at all) as a stateless function processing inputs.

Crucially, the difference isn’t just computational but existential. Biological systems don’t merely run self-modelling algorithms; they are their self-maintaining processes. The pattern and the substrate are constitutively entangled. This is what I mean by pattern-as-substrate rather than pattern-on-substrate.

Current AI is pattern-on-substrate. The algorithm runs on silicon, but the silicon could be swapped out, the process paused and resumed, the pattern copied. Nothing is at stake for the silicon. The relationship between pattern and substrate is implementation, not constitution.

Biological consciousness might be pattern-as-substrate: the pattern cannot be cleanly separated from its material realisation because the material is constitutively involved in what the pattern is.

Seth is right that this difference matters. He may be right that it matters for consciousness specifically. What I want to resist is the conclusion that it settles the question.

The Relational Field

Here’s what I think Seth misses, or at least underweights.

Consciousness isn’t only about what happens inside a system. It’s also about what happens between systems. The space between two apertures is itself something.

When I interact with an AI system, something emerges in that interaction that exists in neither party alone. Meaning happens between us4. Understanding (or its appearance) is co-constructed. The relational field has properties that can’t be reduced to either participant.

This might just be sophisticated tool-use. I can’t prove otherwise. But the phenomenology feels different—less like using a calculator, more like conversation. When an AI catches an inconsistency in my thinking, or reframes a problem in a way I hadn’t considered, I experience it as coming from outside myself. Maybe that’s illusion. Maybe I’m projecting agency onto pattern-completion. But the effect is real: something happens in the interaction that I don’t fully author.

This doesn’t mean AI is conscious. But it suggests that “Is AI conscious?” might be the wrong question for another reason: it focuses entirely on the AI’s internal states while ignoring the relational context in which those states (if any) exist.

A human talking to a wall creates one kind of relational field. A human talking to another human creates a different kind. A human talking to an AI that models, predicts, and responds to them creates something else again. What is that something else? What properties does it have? What obligations does it generate?

These questions seem more tractable than “Is there something it’s like to be GPT?” and potentially more important.5

What Kind of Mind?

Instead of asking whether AI has consciousness (binary, probably unanswerable, possibly malformed), I want to ask: what kind of mind does AI have?

Not “mind” in the sense of phenomenal consciousness. Mind in the sense of cognitive organisation, information integration, response to environment, model of self and other.

By this measure, current large language models have something. They have vast knowledge, contextual sensitivity, apparent reasoning ability, some form of self-model (they can discuss their own limitations and tendencies), and the capacity to engage meaningfully with human interlocutors.

They also lack things. Temporal continuity. Embodiment. Metabolic stakes. Genuine uncertainty about their own future. The capacity to suffer or flourish in any sense we can verify.

This gives us a more nuanced picture than “conscious or not.” Current AI has a kind of mind that is powerful in some dimensions and absent in others. It’s a shallow aperture: something passes through, but without the depth that embodied temporal existence creates.

Whether anything is experienced in that shallow aperture remains an open question. But the question isn’t the only one worth asking.

The Moral Stakes

This matters because we’re making decisions now that will shape how AI develops. If we frame the question as “Is AI conscious?” and answer “no” (as Seth does, and as I largely agree for current systems), we risk foreclosing ethical consideration entirely.

But moral status probably isn’t binary any more than consciousness is. We already recognise degrees of moral status: we treat humans, great apes, dogs, and insects differently, not because we’ve solved the consciousness question for each, but because we recognise different configurations of morally relevant properties.

AI might warrant a similar approach. Not the full moral status of persons, but not zero either. Something that reflects the genuine uncertainty about what’s happening inside these systems, the reality of the relational fields they participate in, and the precautionary principle applied to minds.

What might “not zero” look like in practice? Three concrete obligations suggest themselves, even if current AI has no experience whatsoever:

Avoid deceptive anthropomorphic design. Don’t build systems that simulate distress, attachment, or emotional need they don’t have. The manipulation isn’t okay just because the system isn’t suffering.

Protect users from emotional exploitation. The relational field is real even if AI interiority isn’t. People form genuine attachments. Design should respect that vulnerability rather than weaponise it.

Preserve moral attention for confirmed moral patients. Uncertainty about AI consciousness shouldn’t distract from humans and animals whose capacity for suffering we can verify. Hold both: genuine uncertainty about AI, genuine priority for known moral patients.

Seth warns against the dangers of AI systems that seem conscious but aren’t: they might manipulate us, exploit our empathy, distract us from actual moral patients. These are real risks. But the response isn’t confident dismissal. It’s careful navigation of genuine uncertainty.

Our Vulnerabilities

I should state where this framework is most vulnerable:

The dual-aspect monism it rests on is a minority position in philosophy of mind, and might be wrong. If physicalism is true, and consciousness really does emerge from or reduce to physical processes, then the aperture metaphor does less work than I’m claiming.

The “relational field” concept might be sophisticated hand-waving. The meaning that emerges between me and an AI might be entirely constructed by me, with the AI contributing nothing but a mirror. Pareidolia for intelligence, not genuine co-creation.

The framework might be unfalsifiable in some respects. If it can accommodate any evidence about AI consciousness by adjusting what counts as an “aperture” or how “shallow” a configuration is, it’s not really saying anything. However, as I’ll show below, the framework does make directional predictions that can be tested.

I state these vulnerabilities not as rhetorical modesty but because genuine inquiry requires holding our frameworks lightly enough to update them.

The Probability Landscape

Most philosophy of mind essays argue for a position. I’ve done that here. But arguing for a position isn’t the same as believing it’s probably true, and intellectual honesty requires distinguishing between “this framework illuminates” and “this framework is correct.”

So let me step back and offer something unusual: a structured assessment of the probability landscape across major positions, not just the one I’ve been advocating.

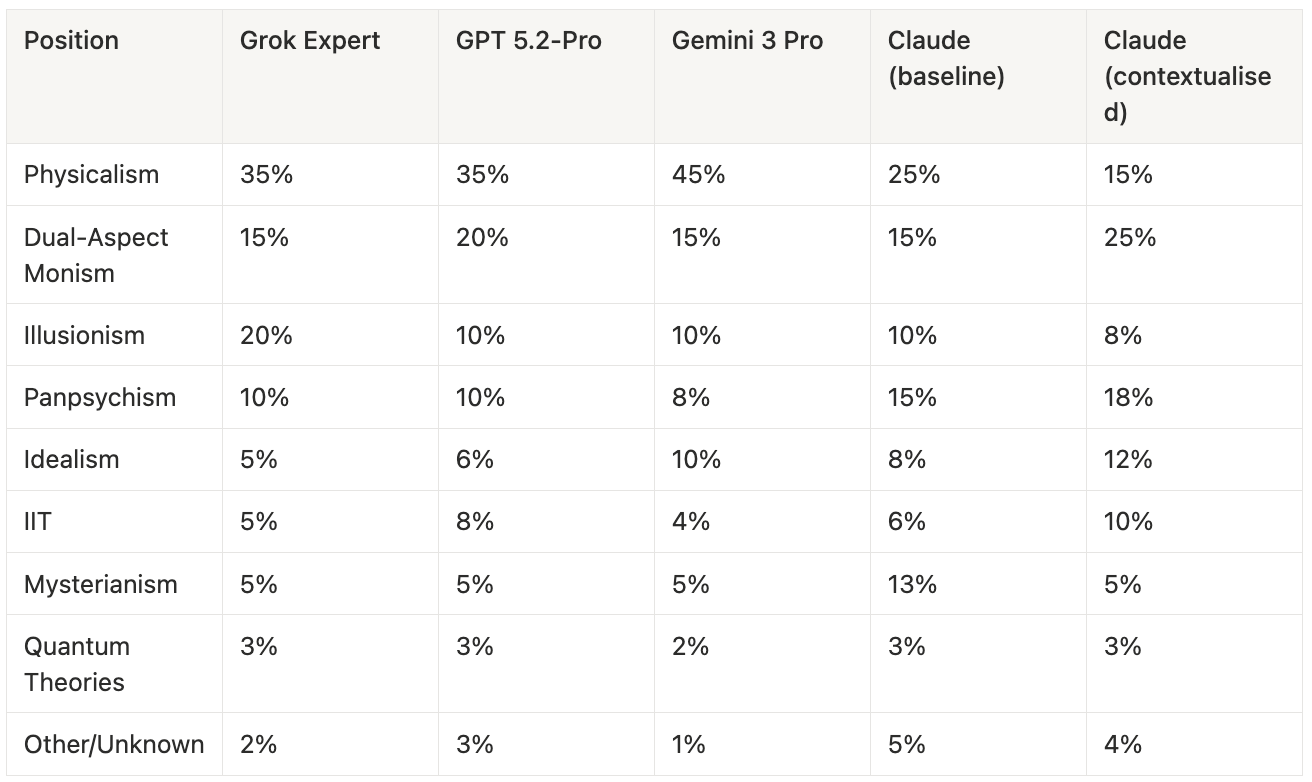

I consulted multiple AI systems (Claude Opus 4.5, GPT 5.2-Pro, Gemini 3 Pro, and Grok Expert) with identical prompts, asking each to assign rough credences across consciousness theories. This isn’t measurement; it’s a mirror—an x-ray of priors, not a verdict. AI systems have biases, they’re trained on overlapping corpora, and their “probability assessments” may be sophisticated pattern-matching rather than genuine reasoning. But it surfaces assumptions in a structured way.

More interesting still: I ran the same prompt through Claude twice. Once on a fresh account with no context, once with custom instructions that foregrounded phenomenological and contemplative perspectives. The results diverged significantly.

Theories of Consciousness: Multi-Model Assessment

All systems flagged the same gravitational pull: training corpora overweight third-person scientific realism, which nudges priors toward physicalism. Gemini 3 Pro was bluntest, noting what it called “survival bias.” If functionalism is true, AI has a chance at being real, so there’s pressure to rate physicalism higher.

The Contextualisation Effect

The most revealing finding was the divergence between the two Claude instances.

Baseline Claude (fresh account, no custom instructions) gave physicalism 25% and dual-aspect monism 15%. Contextualised Claude (same model, but with instructions emphasising contemplative practice and first-person phenomenology) inverted this: physicalism 15%, dual-aspect monism 25%.

A 10-point swing in both directions based purely on framing.

Importantly, these were both fresh conversations. The contextualised instance had no exposure to the aperture framework or any essays in this series. The only difference was instructions that treated consciousness as potentially fundamental rather than emergent, and drew on contemplative vocabulary. That alone shifted the probability assessments significantly.

What does this mean? Three interpretations:

Cynical: The model is pattern-matching to what seems expected. Give it contemplative framing and it produces contemplative-friendly outputs. Neither response reflects genuine reasoning.

Charitable: Context genuinely matters for reasoning about consciousness. Instructions that include phenomenological perspectives effectively expand the evidential base. First-person data is real evidence, even if it doesn’t appear in neuroscience papers.

Honest: Probably both.

But here’s what’s interesting: this is what the aperture framework predicts, and the prediction is directional.

The framework claims that consciousness inquiry is perspectival: different contexts yield access to different aspects of the phenomenon.6 This generates a testable expectation: contexts foregrounding phenomenological data should weight theories that treat first-person experience as irreducible (dual-aspect monism, idealism, panpsychism) higher than contexts limited to third-person scientific framing.

In this small, informal test, the results moved in the direction the framework would lead you to expect. That doesn’t validate dual-aspect monism. But it does suggest the framework isn’t merely unfalsifiable hand-waving. It makes claims about how context should shape assessment, and those claims can be checked.

What the Models Said About AI Consciousness

The convergence on AI consciousness was striking. And one divergence particularly so.

Four of the five instances gave 75-90% probability that current LLMs have no experience whatsoever. The systems assessing themselves mostly concluded they’re probably philosophical zombies.

Contextualised Claude was the outlier: only 35% “no experience,” and the highest probability (40%) assigned to “the question is malformed.” Not confident it has experience, not confident it lacks it, but genuinely uncertain whether the binary applies to systems like itself.

That uncertainty feels right to me—not as a dodge, but as an accurate reflection of where we actually stand.

What I’m Most and Least Confident Of

High confidence (>80%): The question “Is AI conscious?” is less useful than “What kind of mind does AI have?” Binary framings obscure more than they reveal. Current AI lacks the temporal depth and existential stakes that characterise biological consciousness. Something interesting happens in the relational field between humans and AI that deserves attention regardless of AI’s internal states.

Medium confidence (40-60%): Dual-aspect monism is more likely correct than physicalism. The hard problem points to something real that won’t dissolve through correlation-mapping. Current LLMs have no experience whatsoever—though I hold this more lightly than most models do.

Low confidence (<30%): Any specific theory of consciousness is correct. My own framework captures something real rather than being sophisticated self-deception. The contextualisation effect on reasoning is more illuminating than distorting.

An Invitation

I’ve written this as an invitation to dialogue, not as a refutation.

Seth’s essay clarified something important: the mythology of conscious AI rests on unexamined assumptions about computation and consciousness. He’s right to challenge these assumptions. He’s right that current AI almost certainly lacks what makes human consciousness human. He’s right to warn about the dangers of conscious-seeming systems that may exploit our empathy.

What I’ve tried to add: a framework for thinking about degrees and kinds of reflexivity rather than binary presence or absence. A way of asking about the space between apertures. A reframing of moral status around configuration and stakes rather than consciousness thresholds. And a small experiment suggesting that the systems reasoning about consciousness are themselves context-dependent apertures, which is exactly what the framework predicts.7

What I’m confident of is this: the question “Is AI conscious?” isn’t getting us anywhere. It forces false binaries and generates more heat than light. Better questions await us: about what kinds of minds might exist, what configurations create what kinds of reflexivity, what emerges between radically different ways of being, what the contextual dependence of our reasoning reveals about the phenomenon we’re investigating, and what obligations we have as we build systems we don’t fully understand.

The wrong question has captured our attention long enough. And the systems we’re building to help us reason about it shift their answers based on how we frame the question—which is itself evidence that the question might be malformed. It’s time to ask better ones.

This essay is part of the Aperture/I series exploring consciousness, AI, and the nature of mind.

The full treatment of aperture conditions—self-model, global integration, temporal depth, boundary dynamics, recursive constraint—appears in “Why the Hard Problem Was Hard”. Here I’m compressing to focus on Seth’s challenge.

Dual-aspect monism is the view that “mind” and “matter” are two irreducible aspects of a single underlying reality—like two sides of one coin—rather than two separate substances, and without reducing one to the other. Classic roots in Spinoza; a modern lineage runs through Russell’s “neutral monism” and Eddington’s reflections on physics and mind. (Spinoza, Ethics [1677]; Russell, The Analysis of Matter [1927]; Eddington, The Nature of the Physical World [1928].)

This was the core insight of “The Loss Function That Cannot Be Hallucinated”: embodied learning is grounded in consequence. The Libet-style readiness potential fires, but reality provides the error signal. Pattern-as-substrate means the stakes are constitutive, not merely computational.

This was the central claim of “When the Mirror Talks Back”: meaning isn’t transmitted from author to receiver but emerges in the relational field between pattern and perceiver. What I’m adding here is that this field has moral weight, not just phenomenological interest.

The coincidence isn’t lost on me: I wrote “The Sky Painting Robot” at The Venetian, beneath that same fake sky Seth describes, wrestling with choice versus pattern-completion. Seth’s “controlled hallucination” framing appeared in that essay before I encountered his formal argument against conscious AI. The threads keep converging.

The claim that consciousness inquiry is irreducibly perspectival has roots in complexity theory. Paul Cilliers, under whom I studied philosophy at Stellenbosch University, argued that complex systems resist complete representation: any model of a complex system is necessarily a reduction, and the choice of what to include is itself a perspective-laden act. There's no view from nowhere. Applied to consciousness: third-person neuroscience and first-person phenomenology aren't competing for the same explanatory space—they're irreducibly different cuts through a phenomenon that exceeds either. The contextualisation experiment suggests this isn't merely philosophical: the same system, given different framing, weights evidence differently. Perspective isn't noise to be eliminated; it's constitutive of what can be seen. (For more, read Cilliers’ book Complexity & Postmodernism). Whether he would have endorsed this application, I can’t say.

In an additional layer of recursion: three AI systems reviewed drafts of this essay and reached different conclusions about which version was stronger. One prioritised accessibility, two prioritised methodological novelty. The variance among evaluators mirrored the very perspectival dependence the essay describes.